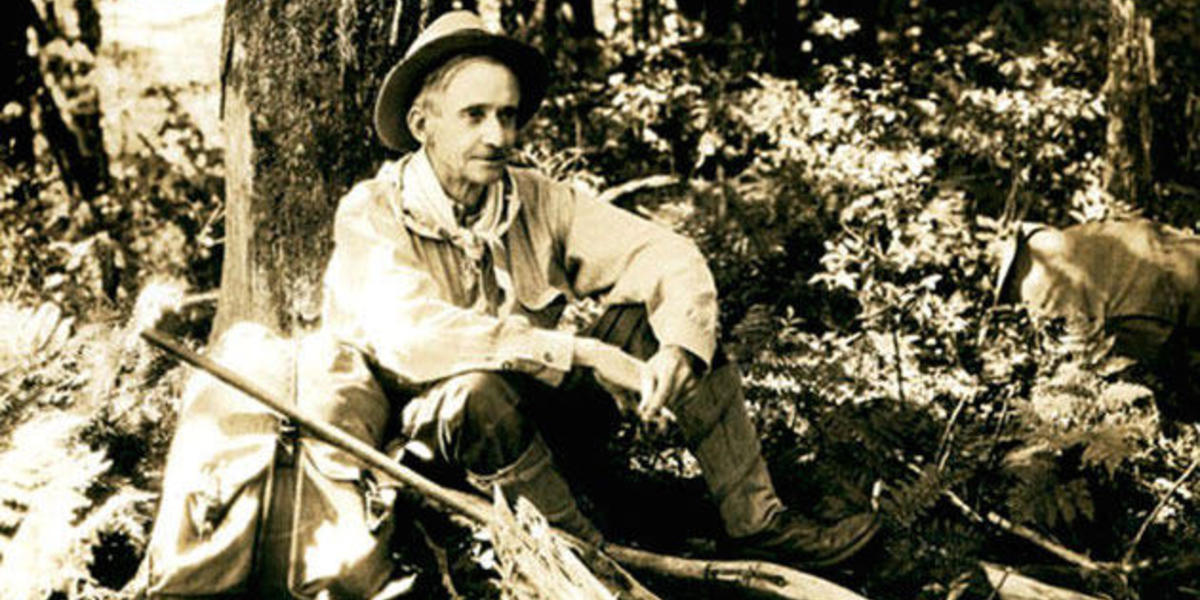

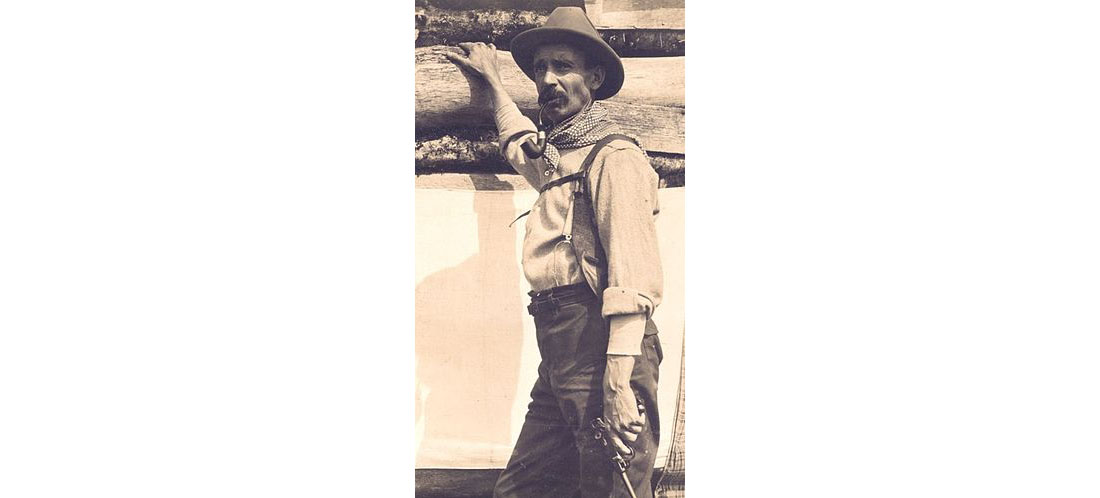

Horace Kephart and The Winding Road to Help Establish The Smokies As A National Park

Most people who visit the Smoky Mountains every year have no idea of the history of the National Park. However, some have heard of some names that ring a bell when exploring the various trails located within the Park boundaries. The Kephart Prong Trail, which crosses over the Oconaluftee River no less than six times, is named after a key figure in the creation of The Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Horace Kephart was a man who seemed to make as many turns in his life as his namesake trail does. His story paints a picture of a man who didn’t give up. He didn't let these mishaps distract him from following his true purpose in life.

Early Life

Horace Kephart was born in Juniata County, Pennsylvania in 1862. His parents were Isaiah Kephart and Mary Elizabeth Sowers. However, he was raised in Iowa after the family moved in 1867. At 17 he entered college at Cornell where he took a position at the library. Here he met Willard Fiske--a librarian and scholar who took the young Horace under his wing. Kephart would follow Fiske back to Italy where he would catalogue his personal library. A few years later he returned to the United States to take a librarian position at Yale University.

Librarian

Life would begin to settle down a bit for him as he got married in 1887 to Laura Mack. They married in Ithaca, New York. However, that wouldn’t stop him from taking a prestigious position as head librarian at the St. Louis Mercantile Library. This is where his studies in early western explorations become more transparent. He started building the library’s collection of Western Americana. His writings were also taking shape as well. He published articles in various publications that are considered vital to the advancement of library sciences. His writings would begin to garner some attention as he would humorously describe his day doing reference work and cataloging obscure books; this would be published in Harper’s Weekly and Library Journal.

Kephart’s writings would gain more attention in 1893. He had several more of his works on library science published. These included “Paste for Labels, With a Word About Writing Inks,” “Bindings in Libraries,” and “Classification". An article on “Classification” was written for The World’s Library Congress Report.

At the turn of the century, Horace Kephart would apply his knowledge of western explorations by getting his booklet on Pennsylvania’s role in winning the west published by the St. Louis bureau of Publicity of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition.

Turbulence in His Life

This time period would prove to be the most turbulent points in his life. With his marriage crumbling, Kephart turned to drinking. He would also take frequent camping trips that would anger the library’s Directors. He would then resign his position. His wife and six children at this time left him. This put him at a crossroads in his life once again.

Kephart would return home to his father in Ohio. He began to declutter his mind. He went through a period of self reflection that he felt he desperately needed after living the fast paced urban lifestyle. His purpose in life would lead him to western North Carolina. After suffering a breakdown in his health, he decided that this was the perfect place for him to recuperate. He abandoned the professional life that led to his “rock bottom”. Kephart had been searching for a life where he could be one with nature. He wanted to be doing plenty of hunting, fishing, and exploring new territory.

Writing

Inspired by his newfound freedom and no longer burdened by the daily stresses of his previous life, Kephart began to churn out writing that reflected the lives of people living in Southern Appalachia. One of these famous works would be Our Southern Highlanders. The setting specifically takes place in the remote Hazel Creek area on the slopes of Silers Bald. Kephart’s cabin was located at Little Fork, and at that time, the nearest railroad depot was 16 miles away at Bushnell. This work tells of firsthand observations through ten years of living and journal-keeping of daily life in the mountains.

Appalachia Controversy

Also this book includes vivid descriptions of bear hunts. It described how women supported the family in the years before the National Park was even an idea. This work has been well-received, however these same vivid descriptions sometimes have projected some critics. This included some folks in Appalachia.They said his descriptions paint a negative stereotype of the Appalachian people. Also, they suggested that he sensationalized his ordeals in order to sell more books. It is still regarded as an important piece on mountain life.

Another of Kephart’s famous works is The Book of Camping and Woodcraft. It was released in 1906 by Outing Publishing Company. This would become an immediate success. It went through a handful of editions over the next decade. That was until The Macmillan Company bought the rights and became their prize. It is referred to as “the Bible of Outdoorsman” and was also issued to boy scout troops all over the country. It helped them gain essential knowledge that are keys to outdoor life. With total sales of hundreds of thousands of copies sold, it’s hard to argue the book’s impact on many people’s lives--even in 21st century America where electronic devices reign supreme.

More Publications

Horace Kephart would continue his work writing for Outing Publishing Company and getting many articles on outdoor life published. He even contributed articles to magazines many people today would recognize. This includes Field and Stream, Forest and Stream, Sports Afield, Recreation. In 1918 Kephart would begin to write for All Outdoors magazine, and his articles would become a highlight of the publication. These articles spotlighted his expertise with guns in the wilderness. His multi-part series, “The Story of the Gun,” was one such representation of this, and it ran until 1919. After this extremely successful period in Kephart’s life where he saw much of his writing published in widely distributed magazines, he came to a point where he was disturbed by what was happening to the Smoky Mountains. This became the next turn in his life--a turn toward activism.

It is important to note the activities going on in the Smokies prior to Horace Kephart and others’ contributions toward making it a National Park. The Little River Lumber Company was responsible for cutting down many thousands of trees in the Smoky Mountains. They turned the landscape barren during the first part of the 20th century.

Little River Lumber Company

Most trees were cut down the old-fashioned way with a hand saw as workers toiled long hours. They found a home in the communities that were founded because of The Little River Lumber Company: Elkmont and Tremont. Most of them worked six days a week but they rarely complained. After all the company offered them a good life--a life that most workers described as a happy life too.

The LRLC wasn’t the only business in town. Many other logging businesses worked nearby cutting out wide swaths of trees in the Smokies. They wiped out about two-thirds of the Park. In 1924 a deal was struck with the state of Tennessee to allow The Little RIver Lumber Company to log part of the Smokies for 15 more years in exchange for ownership of their 75,000 acres. The work, however, was far from done. Horace Kephart and dozens of others would continue their efforts to make it a National Park. This was as loggers continued to strip the land.

Persuasive Influence

Kephart was extremely disturbed by what the logging industry was continuing to do to the surrounding mountains. Even though he was generally a modest man who rarely sought the limelight, he used his talents as a writer to become a very persuasive voice in convincing people locally and nationally of the need to preserve the forests and create a National Park. Along with more than a few people who shared his views, he set out to preserve the 100,000 acres untouched by the logging industry.

One person who joined in the effort to preserve the Park was Japanese-born George Masa. His path toward meeting Kephart began after he was promoted to the valet desk at Grove Park Inn. This was an Asheville, North Carolina luxury hotel. The hotel’s guests became very fond of him as he took a side job processing and printing their film. This ultimately led to him starting his own photography business. He found the Smokies to be an endless inspiration and opportunity with its many dazzling shots of the mountains.

When the chamber of commerce began to use his photos to promote the region, it caught the attention of Horace Kephart. He sought out Masa as a partner in his cause. It didn’t take long for the two to become friends. Kephart got an added jolt of inspiration writing texts of Masa’s beautiful photos. They were constant companions as Masa immersed himself in the flora, fauna, and history of the Smokies.

He became inspired by Kephart knowledge of outdoor life. Their partnership would lead to boosters of the cause for starting a federally funded Park. They raised money for publication of a booklet of their work.

Three Parks in the South

In 1926 Congress announced that three parks in the South would be created with a fundraising goal of $10 million. But the money would not be coming from federal dollars; they wanted the contributions to be raised through private and state funded donations. Many everyday people joined in the cause, opening up their hearts and bank accounts with graciousness. Remarkably, many of these monies came from people who were considered far from even middle class status. With Masa and Kephart’s help too, $5 million had been raised by 1927. However, another $5 million was still needed to reach the goal of $10 million needed to save the Smoky Mountains.

In the meantime, the logging companies were ramping up their efforts by cutting down as much of the forests as they could before they were forced out. Fortunately, philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr. saw what Masa and Kephart had done for the land. When he was told of the environmental distress caused by the fierce logging in the Smokies, he donated the remaining millions to reach the goal. Even though the logging companies--who owned much of the land--wouldn’t go quietly, they eventually all left the Park, leaving it quiet for the first time since the last century. Sadly, that also meant the inhabitants of the land had to leave as well. This included the same people that Kephart wrote about in his writings.

Advocacy for the National Park

The National Park designation was inevitable, but it was a bittersweet time for Horace Kephart in reflection. He was really not at ease with his beloved mountains being taken over by tourists. However, he knew that it was better that the forests and the land was now going to be preserved. This pleased him.

In 1931 Kephart would gain recognition for his contributions in writings and advocacy for the National Park. The U.S. Geological Board named a peak Mount Kephart--located close to the Appalachian trail and the ninth highest peak in the Smokies--to honor him. It was an honor that was previously only awarded to an individual, posthumously.

Kephart would not live to see the Great Smoky Mountains dedicated. He tragically died in a car accident at the age of 68. He was travelling on a mountain road near Ela, North Carolina with fellow author, Fiswoode Tarleton. His close friend, George Masa, was devastated by the news of his death. He died just two years later, suffering more hardship by losing his money in the stock market crash.

Conclusion

Even though he was a complicated man who was no stranger to controversy in his life, he is an endearing figure to many groups. He became an icon and a champion to outdoor clubs everywhere. He was recognized for his contributions which are far ranging and detailed. There were many people who devoted themselves to making the Great Smokies a National Park. However, few have made the impact on that very same ground he lived on for many years. Horace Kephart’s legacy remains, as does his many publications that are still in print today.